Definition

N Engl J Med. 2006 Jul 6;355(1):51-65.

Malignant skin neoplasm resulting from the transformation and uncontrolled proliferation of melanocytes.

Etiology

N Engl J Med. 2006 Jul 6;355(1):51-65.

Histology

- Melanocytes: specialized pigment cells found in the basal layer of the epidermis that produce and transfer melanin to mitotically active keratinocytes.

- Melanin: a dark pigment produced by epidermal melanocytes that protects the nucleus of keratinocytes from ultraviolet (UV) damage.

Risk factors

Bold indicates major risk factor.

|

Category |

Risk factors |

Mechanism |

|

Ultraviolet exposure |

|

UVB is most carcinogenic. UV causes formation of pyrimidine dimers between adjacent thymine and cytosine bases in DNA. Regions containing cytosine bases are hotspots for C → T transition, the most common type of UVB-induced mutation. DNA excision repair is an endogenous system that cuts out the dimers and replaces them with the original sequence. Xeroderma pigmentosum is an inherited genetic disease with a dysfunctional DNA excision system, predisposing these individuals to melanoma. Mutat Res. 2005 Apr 1;571(1-2):19-31. |

|

Genetic predisposition |

|

25-50% of people with hereditary melanoma have a mutation in the CDKN2A tumour suppressor gene, which leads to uncontrolled melanocyte proliferation. 10% of all melanomas are considered familial. 80% of fair skin and red-headed people carry germline variations in the melanocortin receptor-1 gene (MC1R) which impair the production of melanin (a pigment needed to block UVB radiation); instead, they produce pheomelanin, which gives rise to fair skin, red hair, and no UVB protection. Number of nevi positively correlates with UV exposure and is used as surrogate marker of UV-induced skin damage. It may also indicate a genetic susceptibility to melanocytic proliferation. |

|

Immunosuppression Semin Cancer Biol. 2012 Aug;22(4):319-26. |

|

Melanoma is an immunogenic tumour, meaning that a healthy immune system generates a strong immune response to melanoma cells. A strong intrinsic immune response (lymphocytic infiltration of tumour) and treatment with extrinsic immunotherapy (interferon a-2b and IL-2) have been associated with better prognosis. The only other well-known immunogenic tumour is renal cell carcinoma |

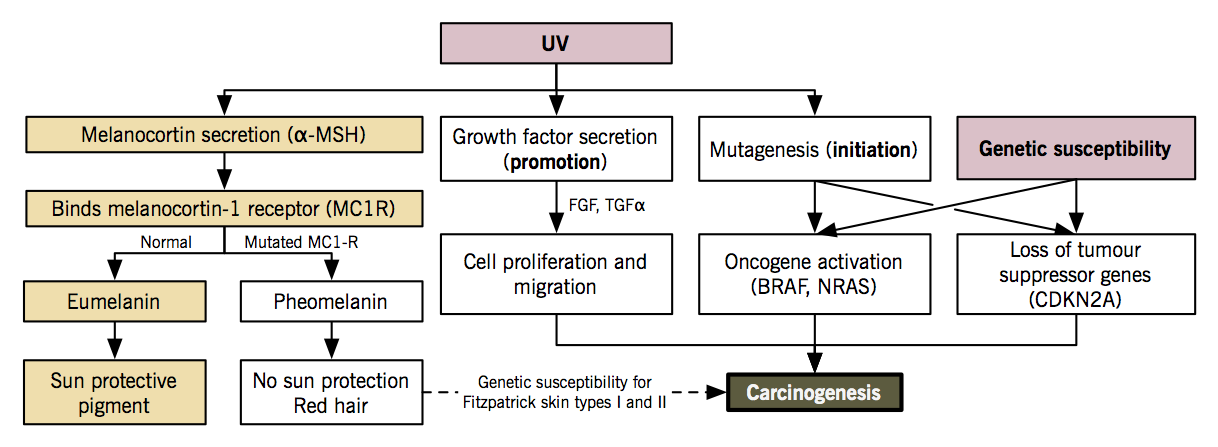

Pathogenesis

Lancet. 2005 Feb 19-25;365(9460):687-701.

- Environmental exposure (UV light) + genetic susceptibility (CDKN2A, CDK4, MC1R, BRAF, p16/ARF genes) → accumulation of genetic mutations in melanocyte that activate oncogenes, inactivate tumour suppressor genes and impair DNA repair → melanocyte proliferation, blood vessel growth, tumour invasion, evasion of immune response, metastasis.

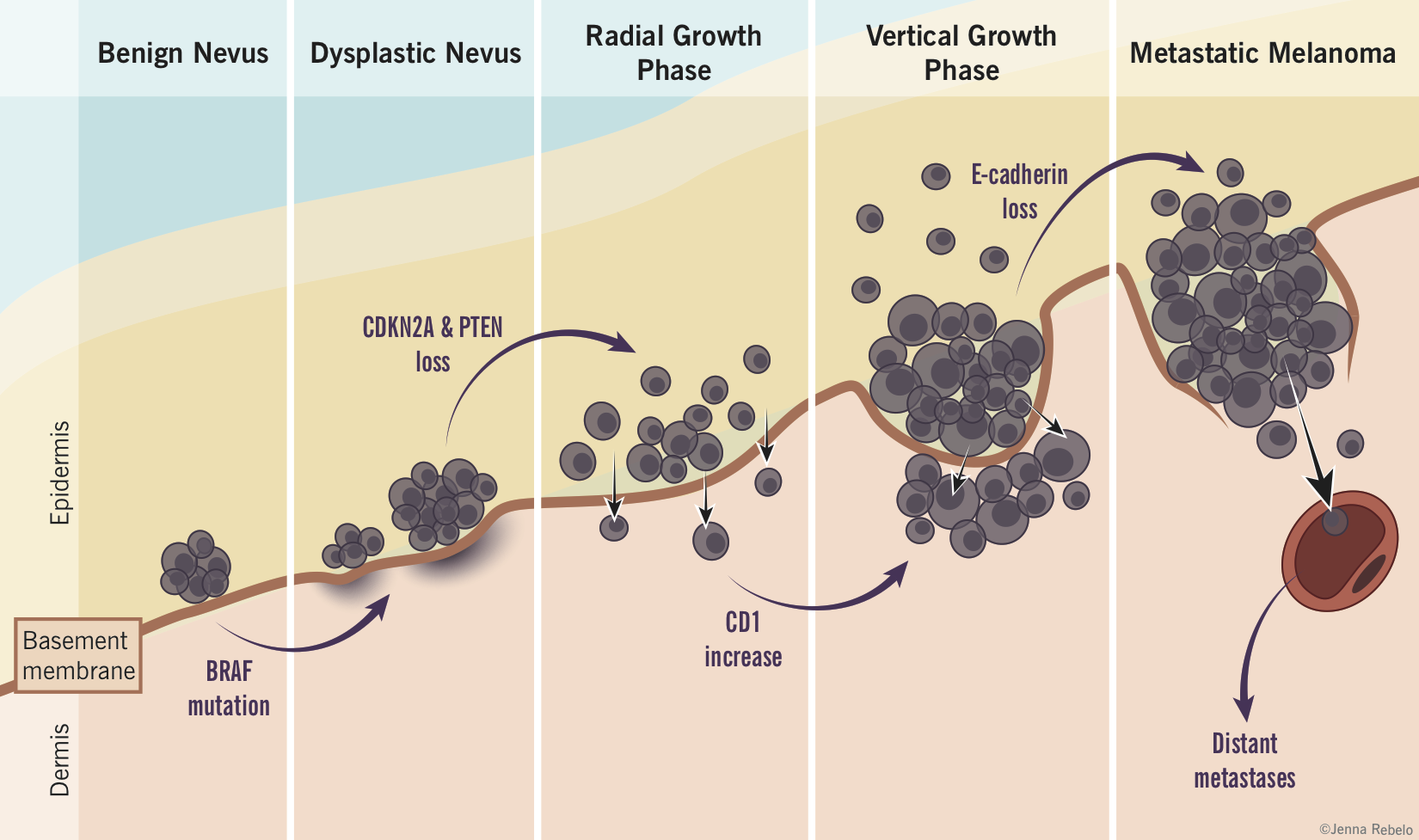

Melanoma tumour progression (based on the Clark model)

- Benign melanocytic nevi: controlled proliferation of normal melanocytes to produce a benign nevus.

- Atypical/dysplastic nevi: abnormal growth of melanocytes in a pre-existing nevus or new location resulting in a pre-malignant lesion with random cytologic atypia. These appear as flat macules, > 5mm in size, with irregular borders and variable pigmentation.

- Radial growth: melanocytes acquire ability to proliferate horizontally in the epidermis and histologically show continuous atypia (melanoma in situ). E-cadherin helps confine the cells intraepidermally but a few cells may invade the papillary dermis.

- Vertical growth: numerous biochemical events including the loss of E-cadherin and expression of N-cadherin allow malignant cells to invade basement membrane and proliferate vertically in the dermis as an expanding nodule with metastatic potential.

- Metastasis: malignant melanocytes spread to other areas of body, usually first to lymph nodes then to skin, subcutaneous soft tissue, lungs and the brain.

Clinical features

- JAMA. 2004 Dec 8;292(22):2771-6.

- Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7e. Chapter 124.

Morphology: ABCDE of melanoma

|

A |

Asymmetry |

|

B |

Border irregularity |

|

C |

Colour variation |

|

D |

Diameter > 6 mm |

|

E |

Evolving (change in size, shape, colour, new lesion) |

Clinical subtypes

|

|

Superficial spreading melanoma (70%) |

Nodular melanoma (15%) |

Lentigo maligna melanoma (10%) |

Acral lentiginous melanoma (5%) |

|

Location |

|

|

|

|

|

Morphology |

|

|

|

|

|

Colour |

|

|

|

|

|

Pathophysiology |

|

*rapidly fatal |

|

*most common subtype in people with darker skin |

Rare variants of melanoma

- Nevoid melanoma: tan, dome-shaped nodule, > 1 cm, resembles a benign nevi.

- Desmoplastic melanoma: firm, skin-coloured nodule or plaque, resembles a scar.

Treatment

- J Hematol Oncol. 2012 Feb 14;5:3.

- Nature. 2011 Dec 21;480(7378):480-9

- N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 2;351(10):998-1012.

- Surgical excision (first line treatment): wide local excision of primary melanoma down to deep fascia. Resection margins are based on the thickness of the lesion.

- Regional lymph node removal: decision to undergo complete lymph node dissection is based on risk of recurrence and results of lymphatic mapping with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Lymphatic mapping involves injection of a coloured or radioactive dye into the primary tumour and seeing which lymph node it drains to, the first of which is called the sentinel lymph node.

- Immunotherapy: since melanoma is an immunogenic tumour, modulation of the immune system may allow the host to better clear tumour cells. Although the following immunotherapies work by different mechanisms, emerging research points to the upregulation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) as an important player in melanoma progression. Tregs mediate self-tolerance and suppresses pathological immune responses. In melanoma patients, (i) primary tumours, (ii) draining lymph nodes, (iii) metastatic sites, and (iv) peripheral blood have all been shown to have increased Tregs, which causes suppression of immune response to the tumour cells. Immunotherapy that reduces Treg counts is associated with clinical response and may prolong survival. Response is often correlated with the production of autoantibodies and proliferation of effector T cells, which both (i) kills melanoma cells and (ii) cause major autoimmune side effects (neutropenia, hypothyroidism, etc).

- Interferon a-2b: adjuvant high-dose interferon α-2b may improve relapse-free survival in high risk patients (stage IIb, IIc and III) who have undergone surgical excision. Interferon a-2b has been shown to deplete the Tregs, allowing other cells to attack the tumour cells and killing them.

- Interleukin-2 (IL-2): high dose IL-2 prolongs survival in metastatic melanoma patients but has severe toxicity (GI effects, hypotension from capillary leak syndrome). IL-2 modulates survival, activation, and proliferation of T cells. Its specific tumour toxic mechanisms in melanoma treatment are poorly understood.

- Ipilimumab is an anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody that prolongs survival in metastatic melanoma patients. Physiologically, cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) is a ligand expressed on all T cells, and ligand binding induces effector T cell suppression. Ipilimumab increases effector T cell activation and proliferation.

- Vemurafenib is a MAP kinase pathway inhibitor that prolongs survival in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with known BRAF-V600E (valine at position 600 is mutated to glutamic acid [e]) mutations. BRAF is a frequently activated oncogene in melanomas. Vemurafenib was designed to bind to BRAF with the V600E mutation only and does not affect cells with normal (wild-type) BRAF proteins.

- Vaccines: several vaccines are in development and some (e.g. gp100) have shown efficacy in advanced melanoma in conjunction with other therapies. Melanoma tumour-specific antigens (e.g. gp100, MAGE) are components of the melanin production pathway that are often overexpressed in melanomas. These antigens are injected into patients, which are engulfed by antigen-presenting cells and subsequently presented to T cells to generate a cellular (CD8+ T cell) and humoral (B cell) response. The activated immune cells target melanoma cells that express the antigens.

Semin Oncol. 2012 Jun;39(3):263-75.

- Chemotherapy: dacarbazine, temozolomide and fotmustine are cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents used to treat metastatic melanoma. Patients show low response rates and no improvement in overall survival. This treatment is reserved for patients who are not candidates for immunotherapy or monoclonal antibody therapy.

- Radiation therapy: used as an adjuvant to surgical excision, primary therapy for mucosal lesions or for palliation.